Viva La Vida

Despite warmer weather, our markets felt cold last week. Maybe it was the never-ending Olympic curling, the overtime hockey matches, or watching snowboarder Chloe Kim secure silver during a blizzard. A notable highlight of an otherwise quiet week was the minutes from January’s Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meeting: Some policymakers warned that the Federal Reserve may need to raise interest rates if inflation continues to stay above the central bank’s 2% goal.

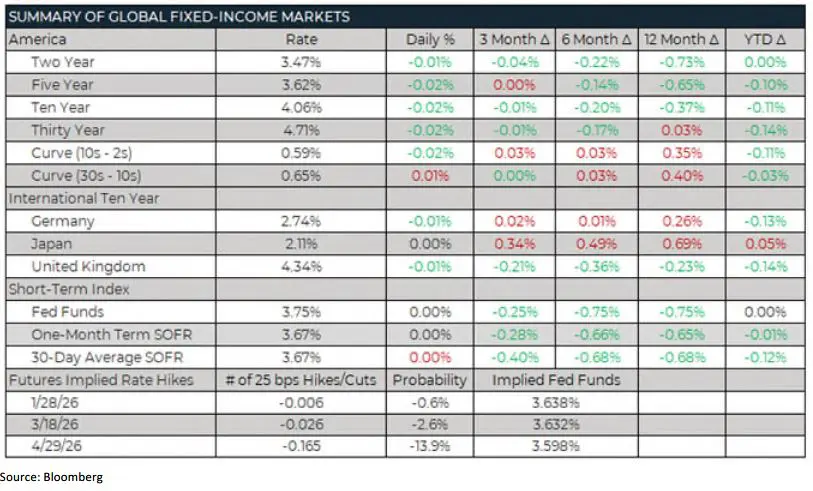

Rate hikes haven’t been discussed much in fixed-income circles, but apparently, “several [FOMC] participants indicated that they would have supported a two-sided description of the committee’s future interest-rate decisions, reflecting the possibility that upward adjustments to the target range for the federal funds rate could be appropriate if inflation remains at above-target levels.” This statement, as well as the Fed’s rhetoric since the FOMC meeting, reminds us that risks remain to the fundamental picture, both to the upside and downside.

Yet at a minimum, those risks don’t warrant near-term cuts. Furthermore, if inflationary pressures do not decline, rate hikes may come back to the table. The “vast majority of [FOMC] participants judged that downside risks to employment had moderated in recent months, while the risk of more persistent inflation remained.” While the FOMC acknowledged a mostly strong economic landscape, underlying details may point to a different story.

Coldplay made headlines last year for the risky (and otherwise questionable) behavior of several of its concertgoers. However, one of the British band’s hits, “Viva La Vida,” foreshadows other risks due to a decline in economic fundamentals. “I used to rule the world, seas would rise when I gave the word,” they sing. “Now in the morning, I sleep alone, sweep the streets I used to own.” This tale of a fallen king echoes the recent tumble experienced by the Leading Economic Index (LEI), produced by the Conference Board.

The LEI was constructed to provide an early indication of significant turning points in the business cycle, as well as offer clues on where the economy is heading in the near term. According to the Conference Board, the LEI’s components include:

- Average work week

- Jobless claims

- New orders for manufacturers for consumer goods and materials

- ISM index of new orders

- New orders for manufacturers for non-defense capital goods, excluding aircraft

- Building permits for new private housing

- S&P 500 index

- Leading Credit Index

- Interest rate spread (10-year Treasury yield minus the federal funds rate)

- Average consumer expectations for business conditions

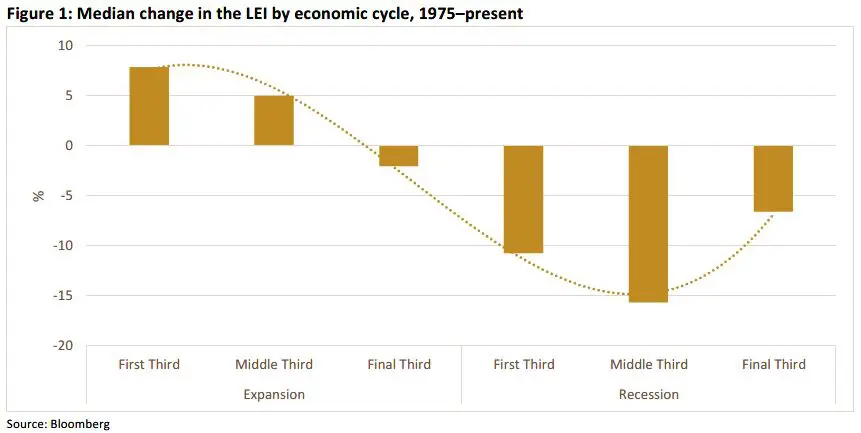

To date, the LEI has been reasonably accurate in providing a quantitative view of where the economy is heading. For a deeper dive, we broke down the index into thirds over both economic expansions and recessions. Figure 1 shows that while the LEI tends to rise on an annualized basis during prosperous times, it declines in late-stage expansions, then snowballs down toward the depth of a recession.

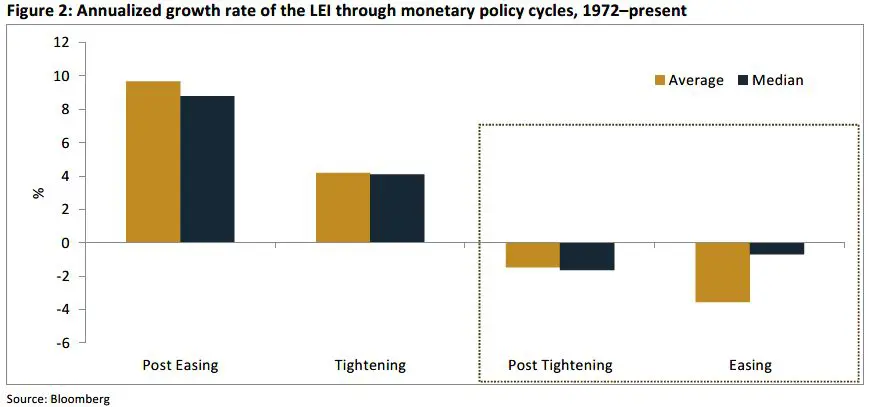

Recessions are typically deemed official by the Business Cycle Dating Committee of the National Bureau of Economic Research some six to 18 months after they begin. So, by definition, this method is less helpful for determining if we’re currently in a recession. That’s why we also cut the same data by monetary policy cycle, which is in real time (Figure 2).

Figure 2 illustrates that in times of prosperity/recovery (post-easing or post-tightening), leading economic fundamentals grow on an annualized basis. Similarly, once the tightening cycles choke off marginal growth, the LEI turns down and declines further as easing cycles take hold (presumably to stave off worsening economic fundamentals). We find ourselves somewhere in the post-tightening to easing stage currently, as the FOMC is technically easing, but at a very slow pace.

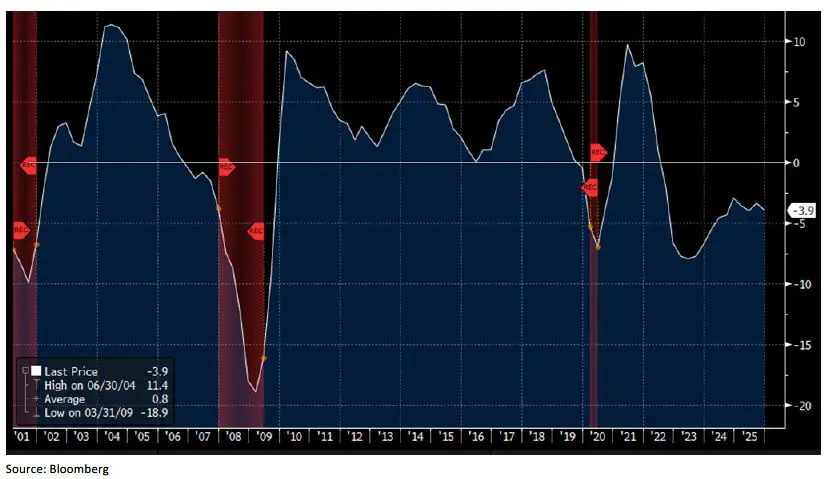

Accordingly, the LEI released last week shrunk for the fifth consecutive month. Additionally, this index has only been positive on a month-over-month basis three times in the last four years. It has also been deteriorating since the summer of 2022—one year before the peak of the FOMC’s aggressive rate-hike cycle, which brought the target fed funds range from 0%–0.25% to 5.25%–5.50%.

Today’s economic landscape has something for everyone. The hawks point to persistent above-target inflation. Indeed, “several participants” said they would have preferred a post-meeting statement that raised the possibility of raising the federal funds rate “if inflation remains at above-target levels.”

Doves, on the other hand, point to indicators like the trend of inflation (not level), the LEI, and softening labor markets. Accordingly, “several officials” remained open to more rate cuts if inflation declined as they expected, though most officials said that inflation progress could be slower than generally forecast.

Ultimately, we think the FOMC will 1) keep to its consensus voting framework and 2) maintain its measured pace of increased accommodation. While the minutes fell far short of suggesting that most officials were contemplating the possibility of rate increases, they nevertheless made clear that the Federal Reserve is shifting further away from agreeing on another cut. Fed fund futures currently estimate that the next 25 basis points cut will occur at the FOMC’s late July or mid-September meeting. As Coldplay might sing, the U.S. economy hasn’t been dethroned, but the Leading Economic Index suggests that it’s no longer ruling with the same authority.

FROM THE DESK

Agency CMBS — Fannie Mae spreads were flat to one basis point wider, week over week, on uninspiring volume. Longer duration mortgage-backed securities (10-years and greater) continue to trade very well. Ginnie Mae spreads were two to four bps wider, week over week, as investors take a two-week break from the continual tightening of the November through January period.

Municipals — AAA tax-exempt yields decreased slightly throughout the yield curve on a week-over-week basis. Municipal bonds have performed well to start the year—largely due to reinvestment of principal and interest paid to investors and strong inflows of new money into bond funds. The combination has created strong demand for new deals coming to market. In the housing sector, we saw short-term, cash-collateralized bonds pricing in the 2.50%–2.75% range, depending on state and maturity. Municipal bond funds had an eighth consecutive week of inflows to start the year ($1.3 billion last week), bringing the year-to-date total to $11.83 billion. The average weekly inflow for 2026 is just over $1.84 billion. Last week’s inflows included $304 million entering high-yield funds.

Looking for more economic insights? Check out all of our previous Trading Desk Talk posts.

The information contained herein, including any expression of opinion, has been obtained from, or is based upon, resources believed to be reliable, but is not guaranteed as to accuracy or completeness. This is not intended to be an offer to buy or sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy or sell securities, if any referred to herein. Lument Securities, LLC may from time to time have a position in one or more of any securities mentioned herein. Lument Securities, LLC or one of its affiliates may from time to time perform investment banking or other business for any company mentioned.